We woke before sunrise, but given the dwindling daylight hours, this wasn’t particularly early. I had set an alarm that I hoped would get us moving in good time without me seeming pushy. I was very appreciative that Con had come to join me and I wanted him to enjoy the walk. This was the first time I had seen him since his wedding the previous month, and in fact he admitted that it was the first time he had been away from his wife for more than six hours. I was very touched that he had torn himself away for this, and I didn’t want to be too punishing a taskmaster. I did need to crack on, however.

The village of Crianlarich lies at the confluence of two glens and a strath. Both are Gaelic-derived words for a valley; the difference is in their breadth, a strath being a broad, shallow-bottomed river valley, while a glen tends to be narrower and deeper. The West Highland Way had an option to go down into the village, which marks its halfway point, but we stayed up on the valley shoulder and turned into a forest, passing another pair of walkers. A brief shower didn’t do too much damage as we trundled along the contouring track, surrounded by green.

After a couple of kilometres, we began to gradually descend towards the bottom of Strath Fillan. We crossed a paddock that was home to some diabetic ponies, followed by a footbridge over the River Fillan, before finding the remains of St Fillan’s priory. Fillan was an eighth century saint with a useful trick up his sleeve. His left arm glowed, giving him the ability to study and write through those long Scottish winter nights, allowing huge savings on candles. He could cure the mentally ill, make his bell fly to his hand, and once persuaded a wolf to take up the workload of an ox it had killed, presumably by playing on its guilty conscience. The priory was restored with a grant from Robert the Bruce, after Fillan’s arm bone had granted him the luck he needed to win the Battle of Bannockburn.

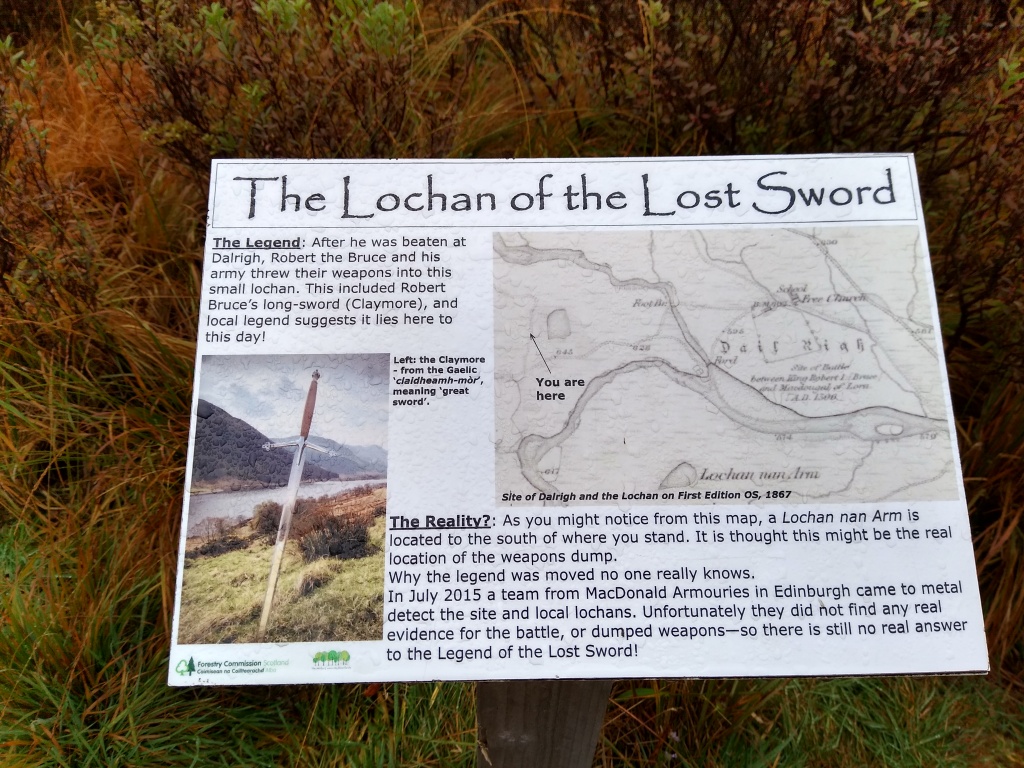

We passed through a campsite where Con bought a coffee, and carried on along the strath floor. A mile along the river, we encountered an information board displaying a tasteful use of the Papyrus font. It told of a legend that Robert and his army had thrown their swords into a nearby Lochan after being defeated in a previous battle. This is just the sort of story I love, and a temptation pressed me to go and take a look in the water. If I did find a legendary sword, though, I reflected, it would ultimately just be one more heavy thing to carry, so we moved on. After passing through another patch of forest for a mile or so, we reached Tyndrum. This small village exists mostly as a waystation, from which a traveller can either head north or west. After Crianlarich, the railway splits into two lines which continue along Strath Fillan, running on either side of the valley. They both stop at Tyndrum, at separate stations, before continuing to either Oban or Fort William, giving it the claim of being the smallest UK settlement with two stations.

Although the village is well set up to serve walkers of the Way, I didn’t want to tarry and we pressed on through into the northbound glen. The steep sides of Beinn Bheag and Beinn Odhar draw together narrowly so that road, railway, and footpath run right alongside each other. The mountains round here are tall enough that they would be hiking hotspots anywhere in England, but Scotland is so spoilt for choice that these are overshadowed by their more famous cousins in other ranges. I wasn’t even taking much notice of them; as close to them as we were, they more or less formed bracken-covered walls around us, disappearing up into the cloud.

It suddenly seemed a bit chillier, and we layered up and sat down for a bite to eat. I know I am repeating myself, but my feet were very sore. Con hadn’t done any walking for a while, and his were beginning to feel it too. On our next section, I showed him the songs on my phone I had been using to force myself on at a quick pace. The valley opened up ahead of us, and we had a long, straight march alongside the railway to Bridge of Orchy. We passed a few highland cattle lying contentedly down by the river.

Perhaps a couple of kilometres from Bridge of Orchy, we spotted a couple of walkers far ahead of us, and Con decided we should overtake them before reaching the village. Accordingly, we set ourselves a quick march, passed them with a “Good afternoon!” just before crossing under the railway line to the station, and then quickly sought a pub to recuperate in. We spent at least an hour in the Bridge of Orchy Hotel, with a drink, a bowl of chips, a sticky toffee pudding, a pack of cards, and our boots off. As we were about to leave, the couple we had said hi to outside Crianlarich came in. I recommended the sticky toffee pudding, and the woman said she had never heard of it before. I felt very sorry for her, but hoped she was about to open up a new chapter in her life.

We crossed the River Orchy over its famous bridge, and reluctantly began to climb. The path left the road and railway behind, taking us up to the shoulder of a mountain with a beautiful view over Loch Tulla. Beyond the loch to the north-east, the land rose gradually to three low hills, standing guard on the southern end of Rannoch Moor.

When I was about twelve, my family broke with our habit of going on holiday to the same places every year and drove up to spend a few days in Kinloch Rannoch, which, according to dad, was in the ancestral heartland of the Robertson clan. This trip was tremendously exciting for me. I was thrilled to feel that I was descended from fierce highland warriors and that I might have a real connection to such a place, thrilled to see the lochs and glens, thrilled that from my window, I could see the pointed peak of Schiehallion, and thrilled to learn that its name meant “Fairy Mountain”, which seemed to confirm that Scotland was as magical as I imagined. I was thrilled that the hotel served cinnamon doughnuts for breakfast. On one day, we hiked up onto the shoulder of a mountain, and while my parents sat there admiring the view, I said I would just go on a bit further to try to get to the top. When I reached the rise above us, I found that the mountain went on further and further, and I followed. It was only when my sister came running after me to say that I had been gone ages that I reluctantly turned back. We also drove out for a wander on the eastern edge of Rannoch Moor. I remember looking out over its open expanse of bogs and lochans, and deciding it was the bleakest, emptiest place in the world.

The West Highland Way came down to skirt round Loch Tulla, then climbed gradually up for five or six kilometres to the western edge of the moor. Con and I took a break sitting on our bags at the bottom of the slope, before bracing ourselves for the long, though fairly gentle climb. Stepping was painful for both of us now, but we needed to cover more distance if I was going to have a chance of reaching Glen Nevis by the next evening.

The light was dying when the path levelled out at around 310m. I think I would have liked to have got in sight of Glen Coe that day, but I realised it wasn’t going to happen. I was aware that Con was struggling. I adopted an “a bit further, a bit further” strategy, and wished I owned a cattleprod. We consulted the map for possible stopping points and decided we would get to Bà Bridge and assess the situation. It was dark when we reached it. I persuaded Con that we should go on another kilometre, to where Bà Cottage was marked on the map. I sat by the bridge, listening to the rushing of the black river below while Con phoned his wife, and vaguely wondered if I was cruel.

Probably less to my surprise than to Con’s, Bà Cottage was just some low, ruined walls. It was interesting to wonder who had lived there, isolated between the moor and the mountains. The ruin did at least have some flat, dry ground to camp on, and stones to sit on while we cooked. We were 41km from Glen Nevis. My final day of trekking before the ascent of Ben Nevis was going to be the longest of the entire journey. There was at least something vaguely satisfying about this, even if it was going to be a trial.

We enjoyed our food in our lonely little spot, our headtorches tiny specks in the vastness. The roars of a red deer stag were carried to us on the wind, and I remembered that it was rutting season. These made a pleasingly wild soundtrack as I settled in for my penultimate night of the journey. It was the 17th of October, exactly three years since I had fallen, three years since I had lain broken in a hospital bed, wondering what lay ahead of me. Look how far I had come.